Nearly winning is more rewarding in gambling addicts

Pathological gamblers have a stronger brain reaction to so-called near-miss events: losing events that come very close to a win. Neuroscientists of the Donders Institute at Radboud University show this in fMRI scans of twenty-two pathological gamblers and just as many healthy controls. The scientific journal Neuropsychopharmacology published their results last week.

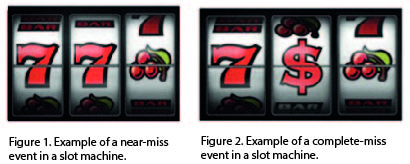

Despite being objective losses, near-misses activate a particular reward-related area in the middle of our brain: the striatum. In the current study, neuroscientist Guillaume Sescousse and his colleagues show that this activity is amplified in pathological gamblers. When compared to healthy controls, pathological gamblers show more activity in the striatum after a near-miss event (Figure 1), than after a complete-miss event (Figure 2). This activity is thought to reinforce gambling behaviour, supposedly by fostering an illusion of control on the game.

To obtain these results, Sescousse compared fMRI scans of pathological gamblers and healthy adults while they were playing a slot machine game. ‘We’ve made our gambling game as lifelike as possible by improving the visuals, adding more sounds and adapting the speed of the slot wheel compared to previous versions. In our game, the chance for a near-miss was 33%, compared to 17% for a win and 50% for a complete-miss.’

Gamblers have a strong illusion of control and they believe in luck more than others when they gamble. ‘It was challenging to find the subjects for this experiment’, according to Sescousse. ‘The prevalence of pathological gambling is relatively low in the Netherlands, and our study was rather intensive. People had to come back to the Donders Institute three times, and they could not have any additional disorders, diseases or drug prescriptions.’

What is happening in the mind of a gambler when confronted with a near-miss event? Sescousse: ‘In normal situations near-miss events signal the fact that you are learning: this time you didn’t get it quite yet, but keep practicing and you will. Near-misses thus reinforce your behaviour, which happens by triggering activity in reward-related brain regions like the striatum. This also happens when gambling. But slot machines are random, in contrast to everyday life, which makes them such a great challenge to our brain. That’s why these near-misses may create an illusion of control.’

Animal studies have shown that behavioral responses to near‐miss events are modulated by dopamine, but this dopaminergic influence had not yet been tested in humans. Therefore, all subjects performed the experiment twice: one time after receiving a dopamine blocker, and one time after receiving a placebo. Surprisingly, brain responses to near-miss events were not influenced by this manipulation. ‘For me, this is another confirmation of the complexity of the puzzle that we are working on’, Sescousse explains.

Reference

Amplified striatal responses to near‐miss outcomes in pathological gamblers

Guillaume Sescousse, Lieneke K. Janssen, Mahur M. Hashemi, Monique H.M. Timmer, Dirk E.M. Geurts, Niels P. ter Huurne, Luke Clark, Roshan Cools [link]

Kantje boord verliezen is meer belonend in gokverslaafden

Gokverslaafden hebben een sterkere reactie op zogenaamde near-misses: momenten waarbij je verliest, maar waarbij de winst heel dichtbij was. Dat laten neurowetenschappers van het Donders Institute van de Radboud Universiteit zien met fMRI-scans van tweeëntwintig gokverslaafden en net zoveel gezonde proefpersonen. Het vakblad Neuropsychopharmacology publiceerde de resultaten vorige week.

Hoewel je objectief gezien verliest tijdens een near-miss, activeren deze momenten een gebied middenin het brein dat sterk betrokken is bij beloning: het striatum. Bij gokverslaafden is de activiteit in het striatum na een near-miss (Figuur 1), vergeleken met een complete miss (Figuur 2) sterker dan in gezonde controles. De onderzoekers verwachten dat deze verhoogde activiteit het gokgedrag versterkt door een illusie van controle op de situatie te handhaven.

Neurowetenschapper Guillaume Sescousse en zijn collega’s onderzochten tweeëntwintig gokverslaafden en net zoveel gezonde volwassenen terwijl ze een gokspelletje speelden in de MRI-scanner. ‘We hebben de goktaak zo levensecht mogelijk gemaakt met mooie visuals, goede geluiden en een aangepaste draaisnelheid van de gokschijf. In ons spel was de kans op een near-miss 33%, vergeleken met 17% kans op winst en 50% kans op een complete miss.

Gokverslaafden hebben een sterke illusie van controle, en ze geloven meer in geluk tijdens een gokspelletje dan andere mensen . ‘Het was een uitdaging om de problematische gokkers te vinden voor dit onderzoek’, aldus Sescousse. ‘Gokverslaving komt niet veel voor in Nederland. Bovendien moesten de proefpersonen drie keer terugkomen naar het Donders Institute en mochten ze geen andere gezondheidsproblemen hebben of medicijnen slikken.’

Wat gebeurt er in de hersenen van een gokker tijdens een near-miss moment? ‘Tijdens normale situaties geven near-misses je het gevoel dat je aan het leren bent’, vertelt Sescousse, ‘nu lukte het net niet, maar met een beetje oefening de volgende keer wel. Ze versterken je gedrag door beloningsgebieden in het brein zoals het striatum te activeren. Dit gebeurt ook tijdens gokken. Maar gokmachines zijn willekeurig, in tegenstelling tot het dagelijkse leven, wat maakt dat ze zo’n enorme uitdaging zijn voor het brein. Dat is hoe near-miss momenten een illusie van controle kunnen creëren.’

In dierstudies is aangetoond dat doorgaan met gokken na een near-miss wordt beïnvloed door dopamine. In mensen was dat nog niet eerder onderzocht. Daarom deden alle proefpersonen het experiment een keer nadat ze een dopamineblokker innamen, en een keer nadat ze een placebo innamen. Het medicijn bleek geen effect te hebben op hoe graag de proefpersonen door wilden gaan met gokken. ‘Verrassend, maar het geeft maar weer aan met wat voor een complexe puzzel we bezig zijn’, aldus Sescousse.

Reference

Amplified striatal responses to near‐miss outcomes in pathological gamblers

Guillaume Sescousse, Lieneke K. Janssen, Mahur M. Hashemi, Monique H.M. Timmer, Dirk E.M. Geurts, Niels P. ter Huurne, Luke Clark, Roshan Cools [link]